From Cabinets to Coffins

Posted: July 14, 2014 Filed under: Birmingham History | Tags: Birmingham, Birmingham History, British History, coffin furniture, Industrial History, Industry, Jewellery Quarter, manufacturing, Museum, Newman Brothers Leave a comment

Possibly Newman Brothers’ first coffin-furniture catalogue, circa 1894. Familiar with brass since 1882, they continued to use this material in their new business venture producing coffin furniture from 1894 onwards. © Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

One of the most common questions people seem to have in relation to Newman Brothers is ‘why did a coffin-furniture manufactory choose the Jewellery Quarter to run their business from…wasn’t that an odd place?’ The short and simple answer to that is no, surprisingly not, but I understand why people initially may draw that conclusion. Newman Brothers were originally brass founders, established in 1882, operating from premises in Nova Scotia Street in what is the Eastside area of town today. As such their business was based on casting an assortment of metal articles, in this case, largely cabinet furniture from molten brass. But by 1894, just over ten years later, they had moved to new premises at 13-15 Fleet Street in the Jewellery Quarter. This move also spelled a slight change in their production line.

Casting ladle from the Newman Brothers’ collection, discovered in what was their tool room. This was probably used to pour the molten metal into cast-iron dies when Newman Brothers were brass founders and certainly during their years at Fleet Street as coffin-furniture manufacturers. © Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

They were now listed as ‘Coffin Furniture Manufacturers’ and specialised in the production of general brass furniture. I say slight change as coffin furniture is, in fact, a natural extension of the jewellery and ‘toy’ trades and their many ancillary trades, using not only the same materials, but also incorporating the same skills and processes to produce various metal goods.

Central to the production of both trades was and is (especially in terms of today’s jewellery production) the drop stamp, which uses heavy metal weights known as dies and punches with chiselled designs, on a pulley system to ‘stamp’ out products. So, the materials, machinery and methods of production were identical in both the jewellery and coffin-furniture trades, with the main exception being that drop stamps for the latter were much bigger, incorporating more weight to produce the larger items. Whether you were making a badge, a breastplate or a brooch therefore, the manufacturing processes involved were the same. The only difference was the intended use of the finished article. In this respect it made perfect business sense for Newman Brothers to relocate to the Quarter, as this new locality positioned it amongst a hive of thriving skills central to the production of coffin furniture, as well as allowing them to continue their tradition of casting.

A Newman Brothers’ registered design from 1884 depicting a cabinet backplate and handle. © The National Archives.

A Newman Brothers’ backplate and ‘swing’ handle from circa 1894-1900. Although a different shape, the familiar form can be seen in its resemblance to the cabinet design on the left of this image. © Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

The company’s transition from cabinet to coffin furniture was equally a natural development rather than a radical innovation in their product line. Take the two images above for example. The one on the left shows an 1884 Newman Brothers’ patent design for a cabinet backplate and handle, and was one of their earlier registered designs as brass founders. The other is yet another backplate and handle, but this time, intended for a coffin rather than a cabinet. Although flora-inspired designs for coffin furniture were common during this period, fauna-based patterns rarely seem to enter the equation. In this respect, the form and function of what Newman Brothers were producing largely remained stable, but the aesthetics of their designs altered to suit the backdrop of their new business.

Brass founders were renowned for making a range of different products and because of the ease with which coffin furniture could be produced, many non-specialist firms could quite comfortably ‘tap’ into this line of business, which means that there’s a good chance that Newman Brothers were already making some goods for the funerary trade before they became specialist manufacturers. No doubt they also had an existing clientele to some degree too, making their transition into the funerary trade smoother, and it would seem that their move from cabinets to coffins was most likely financially motivated. The transient nature of the funeral was simply bigger business than the permanence of home furnishings.

Sarah Hayes, Collections and Exhibitions Manager at Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

Follow progress @HayesSarah17 and @CoffinWorks

A Family Connection

Posted: April 20, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Birmingham, Birmingham History, British History, coffin furniture, Family History, funerary traditions, History, Jewellery Quarter, maps, Museum, Newman Brothers 2 Comments

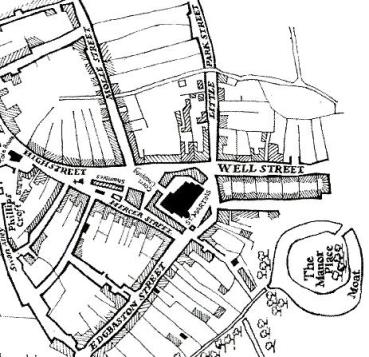

Late 19th-century map showing Fleet Street. Caroline’s daughter, also called Caroline, lived briefly at number 3 Fleet Street in 1891, located near the corner of Newhall Street. Just a stone’s throw away, she may well have seen the construction of Newman Brothers, which began in 1892.

Family history never ceases to amaze me, especially in how we can often unknowingly mirror the endeavours and actions of our ancestors. In fact, a recent discovery of an ancestor working in the funeral trade in Birmingham over 150 years ago, and then of her daughter living on Fleet Street, just ten doors down from what was to become Newman Brothers Coffin Works (my current place of work) is almost poetic symmetry for me. For those unfamiliar with the project, Newman Brothers made coffin furniture for over 100 years between 1894 to 1999 on Fleet Street in the Jewellery Quarter. But failing to meet the demands of changing-industrial processes, largely dictated by the ‘plastics revolution’, as well as simply running out of steam, meant that Newman Brothers finally closed its doors in 1999, leaving everything behind. Everything is the operative word here, because everything from machinery, coffin handles, breast plates, company ledgers to a bottle of whiskey along with cans of soup were discovered. These objects will form the basis of Birmingham’s latest heritage attraction, allowing people to step back in time and experience the history of this company and of this trade.

©Sarah Hayes. My great-great grandmother, Caroline Wilkes, daughter of Caroline Derkin, who was living on Fleet Street in 1891.

My connection to this trade is through my great-great-great grandmother, Caroline Derkin, who at the age of 17 was described as a ‘coffin-furniture maker’ on the 1861 census, the year that Prince Albert died. Discovering that I have a direct connection to this trade through one of my ancestors was a special moment indeed, and has fuelled my passion for this project even further. Coffin furniture covers a broad spectrum of products and as there was a division of labour between genders at this point, it’s most likely that Caroline was either working in the ‘soft’ furnishings division of this trade, making shrouds, linings and other textile-based products, or equally feasible is that she may have been working on the more industrial side, operating fly presses for cutting and piercing metal, another female-oriented role.

In 1851, there were nine master-coffin-furniture manufacturers in Birmingham, but the ease with which coffin furniture could be made, meant that goods could also be produced by a number of other non-specialist metal firms who made similar products, using the same industrial processes.This makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly which company Caroline was working for, but as she was living on Cecil Street in the New Town area of the city, it’s likely therefore, that she was working within walking distance of her home, as was the norm during this period.

The red pin shows the location of where Caroline Derkin was living in 1861 in the New Town area of the city.

But, regardless of where she was working, it’s her connection to this Birmingham industry and more specifically, her direct connection to me and her legacy to my own story, that somehow brings me closer to her, and in a funny sort of a way, is an appropriate epitaph to our family’s history. She made coffin furniture and I’m attempting to preserve it. And it’s exactly that, the personal sense of preserving her story in my endeavours to preserve the history of Newman Brothers’ that has made this project yet again even more personally satisfying. What she’d make of a museum dedicated to the history of coffin furniture 150 years on is beyond me, but the story of Caroline Derkin has brought me closer to a chapter of Birmingham’s history and somehow for me, anyway, legitimised my role in preserving and exhibiting the history of this important Birmingham trade.

Keep up to date with progress @CoffinWorks and via http://www.birminghamconservationtrust.org

Sarah Hayes, Collections and Exhibitions Manager @CoffinWorks

Follow me @HayesSarah17

Who Were the de Birminghams?

Posted: March 19, 2014 Filed under: Medieval History | Tags: Anglo-Saxons, Archaeology, Birmingham, Birmingham History, British History, Medieval, Middle Ages, Normans 3 Comments

An impression of what the de Birmingham manor house may have looked liked in the 13th century. © Birmingham Museums

The 12th century was a period when the popularity of surnames increased and started to become hereditary. One such type was the ‘locational’ surname, which denoted where a person lived or came from. Birmingham is part of that group, as it represents a physical settlement. At this point though, surnames were unstable and likely to change depending on where a person was living or moved to. So, who were the family who assumed the de Birmingham name by at least the 12th century, and primed the town for its later industrial success?

The first reference we have to the de Birminghams is in the 12th century and we know that they were living in a moated-manor house centred upon what was to become Moat Lane car park, hence where the car park takes its name. The Anglo-Norman language had already made its mark on the country by this point, which can be detected by the adoption of the prefixes ‘le’ and ‘de’ before many surnames. This in itself raises an interesting point that many historians have been and are still asking: were the de Birminghams of Norman or Anglo-Saxon ancestry? The answer to that question unfortunately cannot be answered as there simply isn’t enough documentary evidence to state either way, but let’s take a look at what we do know.

It’s been estimated that only eight percent of England’s land remained in the hands of Anglo-Saxons after the Conquest, as the event marked a complete transfer of estates from ‘natives’ to the newly conquering noble class. It seems likely to many historians therefore, that the de Birminghams were most probably of Norman ancestry rather than Anglo-Saxon. However, they weren’t top-ranking nobles so to speak, but part of the middling tiers, so for some historians it’s feasible to suggest that they may have equally been of Anglo-Saxon origin. After all, the first reference of them owning land is from the early 12th century, nearly 150 years after the Conquest, giving Anglo-Saxon families, particularly those with political ambitions, plenty of time to settle in to the fabric of this ‘new’ country. Also, it was often political affiliations that counted, not necessarily cultural, meaning that the latter wouldn’t prevent advancement through the ranks.

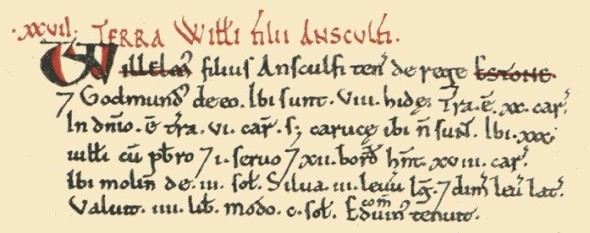

The surname of the tenant holding the manor of Birmingham at the time of Domesday in 1086 was unrecorded; all we know is that his first name was Richard. The first named de Birmingham was a William who was ‘enfeoffed’, or given land in exchange for a pledge of service to his overlords during the reign of Henry I, sometime between 1100-1135. William’s son, Peter, is perhaps the best known de Birmingham as it was his shrewd business sense that secured the town’s growth with his purchase of a market charter in 1166. So, we can confidently say that from at least 1135, and very possibly before then, the family who were to own and cultivate the manor of Birmingham adopted the name of that manor as their own.

The town of Birmingham would eventually ‘burst its banks’ and outgrow not only its own manor, but swallow the many manors around it to become Britain’s second city. © Birmingham Museums

They were, in fact, small fry in regards to their lordly status, and if we were thinking about this in terms of a football league, the de Birminghams were far from Premiership quality, but somewhere in the second or third divisions perhaps. However, they always had their eyes set on promotion with aspirations of climbing the baronial leagues. Impressively, the de Birminghams managed to maintain their status until the fifteenth century when Edward de Birmingham lost possession of the manor to John Dudley, ending their long line of succession.

The de Birminghams were actually the sub lords to the lords of Dudley, and in modern-day terms this meant that they were ‘sub letting’ land from the Dudleys in return for providing military service. They were in effect their vassals or knights and this meant that if the Dudleys needed military backup, the de Birminghams would honour that request, no questions asked. If they failed to do so, they risked forfeiting their land. Nevertheless, they often acted of their own accord, actively participating in foreign military campaigns and even in civil war, most notably as rebels against the eventual Edward I in the Battle of Evesham in 1265.

They certainly enjoyed a life of luxury too judging by the stoneware jar below, which was found in excavations of the moat between 1973-75. It might look modest, but clay analysis tells us that it’s from the Levant region, around present-day Syria and Lebanon, and was once used for storing mercury, a very expensive medicine in the middle Ages.

For middling ranks of the aristocracy they also held a fair few estates including Shutford in Oxfordshire, as well as further afield with lands in Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Closer to home was Edgbaston, which most likely explains why one of Birmingham’s first medieval roads sometime before 1296, was named Edgbaston Street. Presumably this was a sure way of connecting trading ventures between two de Birmingham estates.

The stoneware pot probably dates from the 15th century and was found on the manor-house site. © Birmingham Museums

Of all the estates though, Birmingham remained ‘king’ with its thriving market, as well as being the permanent home of lords of Birmingham. This was where the de Birminghams’ manor house was located after all, strategically situated, so that it was well placed to administer political and social life in the town, as well as serving as a natural meeting point.

The site, which marked the home of the de Birmingham lords since the 12th century was completely redeveloped by 1816, with remnants of the house and moat permanently erased making way for the Smithfield Markets, which opened the following year. Today, all that marks the location of Birmingham’s seigniorial birthplace is a 1960’s concrete car park that now sits on the periphery of the city centre, forgotten by most, no longer in the heart of civic life.

Depiction of the Moat Square development from Birmingham’s Big City Plan. © Birmingham City Council: http://www.birmingham.gov.uk/bigcityplan

But, fortunately we can end on a high note because as part of Birmingham’s Big City Plan the site of the de Birmingham home and one of Birmingham’s first buildings, will be ‘resurrected’ in an upcoming future development. A new public space is being planned called ‘Moat Square’ in reference to the de Birmingham manor house and moat, and more exciting still, the boundary and general footprint of the moat will serve as a new water feature, returning it part way to its original purpose. It seems that the historic heart of the city, which has lay dormant for over 200 years is due to make an imminent ‘come back’ and breathe life back into Birmingham yet again.

Follow me @HayesSarah17

Medieval ‘Footprints’ in Birmingham

Posted: July 25, 2013 Filed under: Medieval History | Tags: Archaeology, Birmingham, Birmingham History, British History, Burgage, History, London, maps, Medieval, Middle Ages, Museum 5 CommentsThe title of this blog doesn’t refer to the sort of footprints you leave behind in the mud or snow, but rather the type that define the area or space occupied by a building, or in this instance the boundaries of a burgage plot. By ‘burgage’, I’m referring to the long and narrow strips of land arranged along street frontages that functioned as the basic units of a town that could be built upon.

So perhaps footprints isn’t the best word to use, because I’m actually referring to plot boundaries rather than the actual buildings. But, footprints is, in another sense, an appropriate word to use as it calls to mind the idea of ‘evidence’ left behind and that’s exactly what the landscape historian and archaeologist has to work with when attempting to reconstruct medieval towns. For a city that’s never been overly keen on preserving its most recent heritage, it might surprise you to learn that Birmingham has some of these medieval ‘footprints’ left.

Burgage plots were characteristically long and narrow, but pressure to subdivide land on account of prosperity and population growth resulted in subdivision of plots making them smaller as you can see in the top right-hand corner of the image. © Birmingham Museums

There are around several of these medieval burgages left in the city centre located in the Digbeth area of town, which appear to conform to their original 13th-century boundary lines. The idea of property boundaries surviving is probably slightly underwhelming for a lot of people, who’d much rather see the actual medieval buildings, but the boundary lines are largely, in fact, an older remnant of medieval towns. Moreover, their story of survival is a fascinating product of the early legal status our ancestors attributed to land. After all, it was owning land, a burgage, that made a townsperson a burgess giving them particular privileges like participating in the collective decision-making of a town. Burgess is in fact, derived from the word burgage which itself comes from the Old French word, burgeis, simply referring to an inhabitant of a town. Buildings, although more appealing, were the dispensable attributes of a property, as they came and they went, but land was preserved precisely because of its power to bestow status on a person, and not to forget its potential to make them money.

The frontages of Birmingham’s surviving burgages located in Digbeth just off Park Street. © Sarah Hayes 2013

We need look no further than London after the great fire of 1666 to help explain how and why burgage plots survive. This event brought disastrous consequences on the city burning down a third of London with an estimated ninety-thousand people displaced.

But for some like Sir Christopher Wren and the Royal Society, this was a golden opportunity. They proposed to rebuild London on the basis of an ordered grid system in place of the disordered medieval streets, but this didn’t happen for a few reasons. First, a complete redesign would have taken too long but more specifically here, the property boundaries, although now virtually impossible to pinpoint on account of the absence of the buildings, were still protected by law.

Map of London in 1593. Notice the disorder of the medieval streets. Source: http://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/England/London/Maps-of-London/London-Maps.html

In fact, it would have involved intervention by the government to implement a complete redesign, and the difficulty of compensating people or transferring their property was a messy and complicated task. The actual reality of rebuilding London after 1666 involved surveyors like Robert Hooke walking the charred streets with residents, armed with available property deeds as well as twine and wooden posts to ‘stake’ out their original plots of land. This example serves to illustrate how legality ensured longevity. That’s to say, that it is precisely the early legal status assigned to boundaries that ensured their survival very often into the 19th century and as recent as the present day in many cases.

Sir Christopher Wren’s proposal for London after the Great Fire of 1666. Source: http://www.architecture.com

‘So what’ I hear some people say, but when you appreciate that we have a stretch of original medieval burgage plots still in Birmingham, standing on the same 13th-century boundary lines, that is a remarkable feat of survival by any standards. What fascinates me the most about this survival though, is that these plots would have been carefully measured out by some of Birmingham’s medieval residents using the town’s very own measuring rod or pole to achieve the intended widths and lengths. These boundary lines, now official, would have been recorded in court rolls and subsequent deeds of transfer. In 13th-century Birmingham one of these plots would have cost you eight pence or four pence for half a plot, incidentally much cheaper than the one shilling fee in other parts of the country.

An impression of what we think the Digbeth plots looked like in the 13th century. Located in the heart of the town, this was a prime spot and the pressure to build here must have been great. © Birmingham Museums

Likewise, burgage widths vary a great deal across the country. In Birmingham, they were probably originally around five metres wide and anything up to 60 metres in length, but in Stratford-upon-Avon the average plot was around 15 metres wide! If you’re lucky, these exact widths and lengths are recorded in official documentation like borough charters as in the case of Stratford. But as Birmingham doesn’t have a borough charter, how do we know that these properties are standing on the same original medieval boundary lines?

We can see what original burgage plots would have looked like when a town was first laid out as illustrated at the top of the image. Once a town started to prosper, plots were subsequently subdivided as depicted in the bottom half of this image. Source: Ideal and Reality in English Episcopal Medieval Town Planning, T.R. Slater

Good question, and the answer is a mixture of hypothesis and fact. Local specialists like George Demidowicz used a technique known as deed regression, which involves tracing boundaries back as far as possible by using property deeds. Such documents record the positions and measurements of a townsperson’s land and luckily for Birmingham, we have a handful of surviving deeds which reveal the transfer of ownership for some of the town’s residents. But this isn’t the case for the entire original medieval town, as we only have this information for sections of the buildings around the Digbeth plots. The deeds tell us that the owners in this part of town ranged from early forms of local government like the Guild of the Holy Cross as well as prominent townspeople such as the Inge and Phillips families.

Specialists also turn to map regression, a technique that uses maps from different periods to compare changes over time and also to identify any continuity. By continuity I’m specifically referring to boundary lines that look ‘ancient’. This involves identifying classic parallel sequences of long strips of land which are often found on19th-century maps denoting the presence of burgages. If these same long strips are visible on even earlier maps like tithe and estate records, there’s a very good chance that we are looking at original burgage plots as laid out when a town was founded. A town’s layout up until the 19th century was often very stable and reflected the original burgage pattern of a town. And although burgages were subject to internal divisions, these later divisions did not normally alter or remove earlier boundaries. This has proven to be the trend across the country. In York, for example, burgage boundaries have survived unchanged from the tenth century, and when plot boundaries were eventually destroyed due to new developments, this change normally occurred in the second half of the 19th century.

A classic burgage pattern depicted on a 19th-century map. This sequence of burgages has since been displaced by modern developments and lies somewhere underneath Selfridges. Also note how the plots have been subdivided, but the earlier original boundary lines nevertheless survived.

In many instances, therefore, we can be sure that when we see long and narrow strips of land on 19th-century maps in places with a medieval past, there’s a very good chance we are looking at some of the original property boundaries of a town. Although the majority of property deeds we have for Birmingham only stretch back to the 1500s, the same rule applies as above: if map regression demonstrates that burgage boundaries do not alter until the 19th century, there’s no reason to suppose that they would have altered by the 16th century. That’s where hypothesis comes in, but this hypothesis is based on detailed research as well as numerous case studies from around the country. Although we can’t actually legitimately trace the Digbeth plots back to the 1150s when Peter de Birmingham founded the town, we can, with the help of both map and deed regression along with the presence of 12th and 13th-century archaeology from the plots, confidently place them at the very latest in 13th-century Birmingham. What is even more satisfying though, is that the forthcoming £150m Beorma Quarter set to transform the area with a 27-storey tower as well as 600,000-square feet of offices, retail and leisure space, will still retain the existing boundaries in the design of the new development. So fortunately, it looks like the medieval relics have a long life ahead of them yet!

A proposal for the forthcoming Beorma development. The new development will be constructed on the same medieval boundaries thereby maintaining around 700 years continuity. Work is due to begin in September this year and will start with the construction of a hotel and the refurbishment of Digbeth’s grade-II listed cold storage building. Source: http://www.trevorhorne.com

Birmingham’s burgages are an incredible vestige of our medieval past in a city that’s rarely been sympathetic to its heritage. For me however, they’re simply special because of their ability to take us back to Birmingham’s beginnings as a recognisable commercial and soon to be urban centre. Just as those London residents who walked the streets with Hooke in 1666 staked their claims and protected their boundaries, this stretch of burgages in Birmingham similarly has the power to evoke the presence of people preparing and planning their very own town. In fact, the truly remarkable thing for me about these seemingly trivial features is the knowledge that around 700 years ago a few of Birmingham’s residents were protective of the very same boundaries we can still see today. In this way these medieval ‘footprints’ serve as a gateway with the power to take us back to the point when Birmingham’s inhabitants were laying the foundations of their town and creating the blueprint of what was to become the basis of this great city.

Follow me @HayesSarah17

Exploring Birmingham’s Medieval Streets

Posted: May 30, 2013 Filed under: Medieval History | Tags: Archaeology, Birmingham, British History, Domesday Book, Feudalism, History, Lord, Medieval, Middle Ages, Museum, Selfridges, towns Leave a comment

© Birmingham Museums. Depiction of medieval Birmingham at the end of the 13th century, with St Martin’s Church sitting at the centre of the town.

A recent talk I gave for the University of Birmingham’s People, Places and Things series of seminars prompted me to write this latest instalment about medieval Birmingham. In fact, it was a question from a member of the audience after I presented the video of Exploring Medieval Birmingham, 1300 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZq9cBzrIVI) that determined the topic of this blog. The person in question asked if I’d thought about superimposing images or footage of Birmingham’s present-day streets over the medieval depictions illustrated in the video. Nice idea, and yes, I did think of doing exactly that, but budgetary and time constraints prevented me from doing so, but that isn’t to say that this can’t be achieved in the near future. Nevertheless, until then this blog will attempt to fill a ‘void’ in going half way to doing just that.

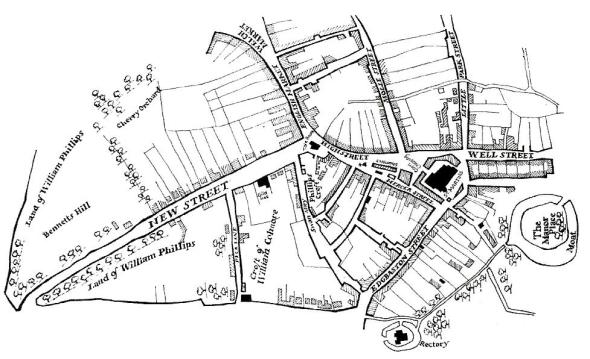

The 1296 Borough Rental referred to in my previous blogs on medieval Birmingham mentions around ten streets in the 13th-century town. Not a bad number, considering that Birmingham had roughly only thirty streets 400 years later. Moreover, some of Birmingham’s best-known streets today were already in existence by 1296. This included the likes of Egebastonstret (Edgbaston Street), le Parkestrete (Park Street), Overparkstret (now Moor Street) Novus Vicus (New Street) and Super Montem (the later High Street).

New Street isn’t as new as we might like to think, but certainly existed by the late 13th century. Perhaps it was only recently new then, but equally it could have been a fixture in the medieval town much before this point. While identifying the streets that framed the town, I started to think about their names especially as they can tell us a lot about an area and its ‘lost’ landscape. It’s easy to forget or simply not realise that the original meaning of street names, much like place names, once ‘said’ a lot about a location.

The many different types of street name can reveal an abundance of information relating to topography or geographical location, natural features, types of industries or even people. It seems that the streets that shaped the medieval town of 1296 were largely ‘signposts’ of locational names or topographical features. One example is Super Montem, translating as ‘Upon the Hill’ and this isn’t hard to appreciate when you realise that this part of town really did and does sit at a higher level than the land leading downhill towards St Martin’s and Digbeth, suitably reflected by its current name, High Street. Then there are the convenient indicators of important trading routes such as Edgbaston Street, named after the Anglo-Saxon manor of Edgbaston, meaning Ecgbeald’s Farm. As Edgbaston was seemingly at one time more successful than Birmingham, as indicated by its higher valuation in Domesday Book, it’s perhaps natural that a road should lead to such a neighbouring settlement. After all, it’s very likely that Birmingham’s inhabitants were trading with Edgbaston’s and vice versa and not to forget that Edgbaston Street led to even more important locations like Northfield. Valued at £5 in Domesday, Northfield was one of the more prosperous manors in the wider area, worth five times as much as that of Birmingham. Moreover it was also once owned by the same overlord as Birmingham: William Fitz-Ansculf whose power was centred on Dudley Castle. So perhaps the street also marked the importance of a wider trading route, as well as leading to Edgbaston itself.

Another important manor also held by William Fitz-Ansculf was Aston, meaning the east estate. Its land and goods were valued at five times that of Birmingham’s at £5 in Domesday Book.

Novus Vicus or New Street is an indicator of Birmingham’s growth and prosperity as new roads were being built presumably to accommodate more inhabitants and trading ventures. Perhaps also, the adjective ‘new’ reflects the age of some of the other streets in the town as they had presumably been in existence for some time to warrant the latest road being called new.

Novus Vicus or New Street is an indicator of Birmingham’s growth and prosperity as new roads were being built presumably to accommodate more inhabitants and trading ventures. Perhaps also, the adjective ‘new’ reflects the age of some of the other streets in the town as they had presumably been in existence for some time to warrant the latest road being called new.

Judging by the question that prompted this blog, people naturally want to know what Birmingham’s oldest streets look like today. It comes as no surprise either that most reside in what is the oldest part of town; the original planned settlement Peter de Birmingham carved out in 1166. This is still one of the busiest parts of Birmingham today bustling with shoppers and inhabitants, now paying their ‘tolls’ and ‘rents’ to a different ‘lord of the manor’. On account of the scale and size we had to adopt for the model of medieval Birmingham, the likes of New Street isn’t featured, so I’ve simply focussed on the streets that are depicted to illustrate what these medieval route ways look like today.

Taken from Birmingham: The Building of a City, the map depicts Birmingham in 1553, but the 12th-century town Peter founded can still be seen. Notice the original triangular shape with four of Birmingham’s earliest roads branching from it: High Street, Edgbaston Street, Molle Street, soon to become Moor Street and Park Street, also at one stage known as Little Park Street.

This brings me on to Edgbaston Street, which in the 13th century was home to surely the smelliest industry in town: leather tanning and judging by the archaeological excavations in the area this trade made the greatest mark upon the industrial endeavours of medieval Birmingham. As an essential material in the Middle Ages, leather goods were a staple of everyday life, as were other goods made from horn and bone, which inevitably grew out of the presence of the tanning trade. Today, Edgbaston Street has exchanged tanning for trading of a different sort, but you can still nevertheless find leather goods, minus the noxious smell, that is. This street is now home to Birmingham’s famous Rag Market, amongst many other traders of mixed enterprise.

By 1553 the Tudor town had spread down New Street and towards the Priory lands of what is now Bull Street.

© Birmingham Museums. The beginning of Park Street in the 13th-century town around where Selfridges is today.

Park Street or le Parkestrete was developed to make way for the many burgeoning industries, thereby cutting into the lord’s deer park, on what was then the edge of town. Although Park Street no longer lines the periphery of Birmingham, it does in many ways mark the edge of its shopping quarter lying adjacent to Selfridges and its attached car park. In this sense, Park Street is still on the fringe of Birmingham for many, particularly the enthusiastic shopper who merely walks this medieval road in pursuit of one of Birmingham’s biggest twenty-first century industries.

The extent of Park Street today, which actually begins around Selfridges’ car park stretching to just past this point towards Millennium Point.

© Birmingham Museums. The beginning of what was to become Moor Street near the eventual site of Selfridges.

Much like Park Street, Overparkstret was also testament to the growth of Birmingham, with the lord once again sacrificing more of his own land for the good of the town, and of course his own pocket. The name is simple and reflects exactly where this new road would lie: ‘over the lord’s park’, or at least part of it. Maybe Overparkstret and Le Parkstret were cut at the same time, maybe they weren’t, but what is clear is that they came into existence to facilitate the expansion of some of Birmingham’s early industries like tanning and pottery making.

Junction of Park Street and Moor Street where we think Roger le Moul held just some of his numerous burgage plots in 1296.

Perhaps the word park in two of the town’s roads which also lay very close to one another was slightly confusing for its inhabitants and traders, as Overparkstret was eventually renamed. In 1344 we find the earliest known reference to its new name: le Mulestret or Moulestret, in honour of the richest family in town, after the De Birminghams, at least. As we know, le Moulestret is today’s very own Moor Street, becoming the second of Birmingham’s medieval streets to accommodate a train station. We arguably have Roger le Moul to thank for this name change, and it’s indeed ironic that his surname translates as the small when we know he was a man of great property. Owning most of the land in town after William de Birmingham, he certainly ensured that his name and his family’s legacy would forever be preserved in his hometown.

© Birmingham Museums. Start of Super Montem or High Street in 1296. This was no doubt used by drovers to bring their cattle to market in the town.

Last but not least, we finish with Super Montem, now High Street, which is only just visible at the very edge of the scale model. True to its name it still sits on higher ground, which is why I always suggest that people make the effort to stand at the top of High Street and look downhill towards St Martin’s Church. Although the natural topography has been slightly distorted by the most recent Bull Ring developments, you can still get a ‘flavour’ of what the medieval landscape once looked like in terms of its gradient.

Almost identical to the previous image in terms of position, High Street today is still bustling with shoppers and in the distance St Martin’s steeple peers up towards the higher ground.

Street names are really an excellent starting point for beginning to understand the physical development and topography of places, and sometimes the most ordinary of names, just like Park Street, lying in the most unassuming parts of town, can with a bit of detective work, really reveal a ‘hidden’ or forgotten history of a place. These muted relics of the past can tell us much more than you’d ever imagine, acting as signposts to a displaced landscape or in some cases subtly pointing to a terrain still very much intact, but obscured by the urbanisation of the modern city. Nevertheless, if we take the time to look hard enough, we can develop these ‘negatives’ in to fully-fledged images and create a colourful depiction of these ‘lost’ landscapes.

Sarah Hayes, Freelance Curator

Follow me @HayesSarah17

From Worcestershire to the North American Plains

Posted: April 10, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: America, American History, Birmingham, Britain, British History, Cavalry, Emigration, Family History, Fort Bayard, History, Native American, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Worcestershire Leave a commentNames like the Battle of Little Bighorn, General Custer and Geronimo are recognisable to most of us on account of the great Western movie tradition that has long dominated our television screens. Most people would name the likes of John Wayne or Clint Eastwood when recalling this genre, but if you’re of my generation, one of the most memorable scenes has to be Marty McFly being plunged back to 1885 in the middle of a United States Cavalry pursuit of Native Americans in Back to the Future, Episode III.

Marty McFly desperately trying to ‘outrun’ the ‘Indian’ charge in Back to the Future, Part III . Source: http://movieclips.com/

It’s the noise of hooves pounding the scorched ground and clouds of dust kicked up in the charge, combined with the familiar sound of Native American ‘war cries’ that defines so many depictions of this genre. Most of my knowledge of this period was previously based on the fictional or half-true accounts portrayed in such films, but now the discovery of an ancestor caught up in the renowned American Indian Wars has truly captured my attention.

It all begins with a boy from Worcestershire, Kidderminster to be precise. Henry Rogers Moorby, my first cousin, four times removed was born in 1853 to Edwin and Rebecca Moorby, who incidentally were married in my hometown of Birmingham at St Martin’s in the Bull Ring. When the Moorbys left England for America isn’t yet known, but the birth of a new addition to the family, by the name of Henrietta is recorded in New York in 1858. From this we can presume that Henry was at least five, but probably younger when he left for America with his family. Three years later the family had moved once again, this time to New Jersey. We’ll never really know why the Moorbys set sail for America but as the 1850s were part of one of the biggest waves of immigration to the US from Europe, we can only assume that they too, were in search of a better life in the ‘great land of opportunity’.

New York in the 1850s and a long way from Worcestershire. Was this the New York that greeted the Moorbys? Source: http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/panel

But this isn’t the part of Henry’s life that’s gripped my attention. Instead I need to skip forward to 1876 when Henry was twenty-three years old. Staying true to his nomadic lifestyle, he joins the army, enlisting with the 4th Cavalry in Jersey City. His enlistment papers describe him as 5’5″, fair complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. This was a time of great land hunger and the strong economic developments such as the railway boom of the 1850s and 60s demanded enormous resources. The population had also been nearly doubling every twenty years from 1800 up until this point and the main task of the US army was supporting the government in ‘consolidating’ the nation. But what did that exactly mean? The ensuing government after the Civil War set out to unify America and complete what many nineteenth-century Americans called their manifest destiny, to conquer land from east to west, thereby sowing their ‘superior’ way of life. The idea of exceptionlism fuelled the policies behind the pioneer settlement and gave justification to the removal of an ‘inferior’ race from this newly-conquered land. The Great Plains, where the majority of the army were based in 1876 were simply the missing link in that manifest destiny.

Columbia, the allegorical representation of America is pictured here in John Gast’s American Progress driving settlers and thus ‘civilisation’ westward to colonise new lands. Source:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:American_progress.JPG

This was frontier land, wild and unruly and ‘up for grabs’ as the US government saw it. The outrage for the many Native American tribes was that they’d been moved here from their native homelands as a result of the Indian Removals Act of 1830. This relocated tribes west of the Mississippi River on what was considered to be poor land with harsh climates, thereby making space for the new white settlers on ‘vacant’ fertile farmland. But east of the Mississippi was quickly becoming overcrowded as the population continued to soar and the insatiable appetite for more territory convinced the government that the lands of the Great Plains weren’t so bad after all. It was this land battle that defined the many struggles of the American Indian Wars.

The missing link in uniting a nation. The red area highlights the Great Plains, traditionally seen as stretching from southern Canada to the southern American states. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_the_Great_Plains.png

As a member of the 4th Cavalry, Henry would have been at the very centre of this conflict as the regiment are known to have been based in the likes of Arizona, South Colorado and New Mexico after 1876; their main duty being to project the pioneer settlers and their lands. But joining the army at this time wasn’t the most appealing of options. It was persistently under-resourced and in 1874 was only 27,000 strong, but responsible for manning two-hundred posts, roughly 135 men if divided equally for each station. The army even made it difficult to spend wages, as troops were paid in paper money which wasn’t yet readily recognised in the West, having to be exchanged at a loss, for coin. Although many recruits may have joined for adventure, it was reported that nearly twenty percent of the army deserted between 1873 and 1876, usually as a result of boredom. Recruits even petitioned Congress in 1878 complaining that their duties simply consisted of building bridges, roads and telegraph lines. But all of these amenities were essential in isolated and vulnerable frontier communities, and the army was crucial in maintaining this new way of life.

Nevertheless there must have been other motivations for joining. The Long Depression had already been raging for three years by the time Henry enlisted and would continue for another three until 1879. One in four labourers in New York and no doubt the situation was worse in New Jersey, were out of work and as a brass moulder, Henry would have suffered the brunt of it. Manufacturing and construction were the main causalities of this recession and with one million unemployed the army must have seemed like a good option. A guaranteed $13 a month for a private in 1876 and the assurance of filling your belly, despite the rations consisting of poor meat, hard bread, beans and strong coffee was seemingly more appealing than life as a civilian.

United States Army recruiting poster, circa. 1876. Source: http://www.crowsnesttrading.com/category/29/2

Another event that presumably acted as perfect propaganda in 1876 was the news of Custer’s defeat at Little Bighorn. But it wasn’t just a defeat, it was an annihilation of 268 men from the 7th Cavalry at the hands of the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors led by Sitting Bull. The reaction was one of outrage and shock, and the timing couldn’t have been worse. The news would have reached the American public during the celebration of the nation’s centennial. America was a hundred years old and for all its economic and political ‘superiority’ it had just been defeated by what many saw as a primitive people standing in the way of natural progression. There’s much more to this story, namely in the fact the Native Americans weren’t primitive at all and grossly underestimated. But the point of mentioning it here is to colour the background and frame the political scene of the America that Henry was living in when he enlisted. The legend of Custer must have played a part in persuading young patriotic men to enlist. Henry did, after all join just four months after the infamous battle and this together with poor economic prospects probably fuelled his decision to abandon civilian life.

Lakota Chief, Sitting Bull, led more than 2,000 Native American warriors against Custer’s 7th Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Source: http://northdakotacowboy.com

The story skips forward here yet again to April 25th 1882, when Henry, now a sergeant aged just twenty-nine years old died ‘of wounds in action with Indians on cars between Lordsburg and Separ, New Mexico’. It was the description of being killed by ‘Indians’ that initially caught my attention and led me to believe that there was something more behind the story. Granted, there were many small battles and skirmishes between cavalry and ‘Indians’ during this period, but even a skirmish can make the newspapers. Lo and behold, a simple search of ‘Lordsburg 1882’ revealed an abundance of sources from books, but more decisively generated newspaper articles, including one from the Sacramento Daily Record-Union reporting on Henry’s death. It places Henry in a conflict with Apaches on April 23rd 1882 that’s frequently referred to as the Battle of Horseshoe Canyon or Doubtful Canyon. Colonel Forsyth, who was present at the battle reported that:

This perfectly supports other accounts from that day, namely that ‘Forsyth raced up with Companies C, F, G, H and M of the 4th cavalry.’ The colonel’s call for reinforcements would spell the fateful demise of Henry as he was caught up in the subsequent gun battle with Apache warriors and shot ‘through the left lung just below the heart; the wound being probably fateful’ and it was. Of course the ‘probably fateful’ explains why he died two days after the attack ‘on cars between Lordsburg and Separ’ as Forsyth sent the wounded by train to the former for treatment. Henry, no doubt was on one of those carriages, dying before he reached the town.

A search of the U.S. Registers of Deaths in the Regular Army, 1860-1889 for Henry confirms his cause of death noting that he died of ‘gunshots of chest’.

Henry’s cause of death noted in the U.S. Registers of Deaths in the Regular Army, 1860-1889. Source: http://www.ancestry.co.uk/

In other accounts, and indeed Forsyth’s own, there is very little about the four Indian scouts and private who were killed. But a simple search of the same register of those who died on 23rd April 1882 discloses the names, confirms the ranks and states the place of death of these five men. Forgotten by history in one sense, they are perfectly preserved in another, and can be ‘written back in’ to this story. Yuma Bill, Kaloh Vichajo, Panocha and Ceguania are revealed as the four scouts, along with Private, William Kurtz, also part of C Company with Henry, who all died at Stein’s Peak on 23rd April. Details around the scouts’ deaths are more limited mentioning only that each had ‘died in action with hostile Indians’ as Yuma Bill’s entry below shows:

‘Indian’ Scout, Yuma Bill or Bill Yuma recorded as dying at Stein’s Peak where McDonald and his contingent were attacked. Source: http://www.ancestry.co.uk/

A search on Ancestry.co.uk of the U.S. Registers of Deaths in the Regular Army, 1860-1889 reveals the five men killed at Stein’s Peak on 23rd April 1882. Source: http://www.ancestry.co.uk/

However, if the passage from the Encyclopedia of Indian Wars below is taken to be true, the circumstances around the scouts’ deaths are all the more tragic as they were initially reluctant to follow their general into Stein’s Peak:

‘Indian’ scouts, Company C Arizona, 1882. They were first authorised as members of the U.S. Army in 1866 and provided vital knowledge of local terrain and Native American tribes. Source: http://www.westernerspublications.ltd.uk

It would be naive to assume that this is an objective account and the phrase ‘cowardly’ is equally problematic, but nevertheless in terms of confirming the number of scouts killed and the presence of Yuma Bill, it perfectly supports the report from the Record-Union. As for William Kurtz, if Henry can be described as ‘lucky’ for surviving two days after the battle, the private was desperately unfortunate being shot in the head and no doubt dying instantly.

Henry’s story ends at Fort Bayard, now a national cemetery in New Mexico where he’s buried. This, however, wasn’t his first resting place as he was reinterred at Bayard on 9th May 1884 having been moved from an earlier point, still to be determined. As for the other five men, no records of their burials appear, but considering that the army would very often bury the dead where they fell, chances are they are resting somewhere very near Stein’s Peak today. Who’s remembered and who’s forgotten has always fascinated me and this story proves not so much that history is written by the victors, but more that rank and position frequently make the headlines. For me, history is an abridged version of the past missing many detailed footnotes. Yet, social history which has been described as ‘the history with people put back in’ has always been my starting point for understanding the bigger narratives of the past. By ‘getting to know’ the likes of Henry and adding names to the nameless, I’m able to appreciate the human story behind this bigger chapter of events. Although we think we ‘know’ history, we are often more acquaintances than good friends, but by trying to understand the actions and motivations of the people involved, just like those in the skirmish of Horseshoe canyon, we can infuse colour back into a faded picture of the past.

Sarah Hayes, Freelance Curator

Follow me on Twitter @HayesSarah17

Exploring Medieval Birmingham: Part II

Posted: August 17, 2012 Filed under: Medieval History, Uncategorized | Tags: Archaeology, Birmingham, British History, Medieval, Middle Ages, Museum Leave a commentThe 1296 Borough Rental referred to in my previous blog is the earliest known ‘census’ carried out in Birmingham. Official censuses didn’t begin in this country until 1801, but recording information about people, land and property has preoccupied governments since time immemorial. We know, for instance, that William the Conqueror commissioned the great land survey, Domesday Book, in 1086 to assess how much his newly occupied country was worth. The Borough Rental was no different in that its main purpose was to keep a record of the rents owed to the lord of the manor. However, like Domesday, it doesn’t give an accurate indication of Birmingham’s population, as it mainly lists principle tenants, those people renting land directly from the lord. William de Birmingham, Lord of the Manor, was in essence a landlord and generated much of his income from renting his land to Birmingham townspeople.

How William de Birmingham made his money! Just some of the burgage plots he rented out to the townspeople.

Our model isn’t just about buildings and institutions in medieval Birmingham, it’s first and foremost about the real people who lived in the town. The Borough Rental doesn’t just record the names of townspeople though. In some cases, it lists their trades and locations. This, together with archaeological evidence from the Bull Ring excavations, has given us a unique opportunity to quite literally trace their footsteps, or at least the general area of Birmingham they called home. We want to allow visitors to learn more about the real townspeople and to ‘interact’ with them through our model.

They can do this through a series of push buttons, which link to eight characters positioned around this interactive. The button will trigger a light and illuminate a character in the model, and visitors can learn more about where that person lived or worked. The characters we’ve chosen represent the wide spectrum of wealth and trades in Birmingham, ranging from the lord of the manor, to everyday folk like tanners and potters.

A tanner scraping skins to remove the unwanted hair.

Archaeology and history go hand-in-hand in this display as the two disciplines combined provide us with an invaluable insight into how people lived. For instance, there will be a selection of cattle horns on display which represent the established tanning industry in medieval Birmingham. The horns also serve to highlight the presence of Welsh cattle drovers who came here to sell their cows at market. With its abundant natural springs and streams scattered around the market place, Birmingham was the perfect place to water livestock. One of our characters, Richard le Couherde, which translates as the cow herder, would have played his part in helping the drovers to guide the cattle to market in the busy town. We know that Birmingham was already at the centre of a well-established road network by this stage, and there’s evidence to suggest that the roads the drovers used were already very old by 1300. Welsh names like Jones, Prys and Brangwayn even crop up in the Rental. While we don’t know if these men were drovers, we can safely assume that they, or their ancestors used these roads to make their journeys to Birmingham.

A cattle horn core found during the Bull Ring excavations in the late 1990s. Horn cores were the only waste product from the cattle, as everything else including the meat, skin and horn were sold.

Birmingham was built on migration and this is a strong theme running throughout the new History Galleries. This trend was well under way in the Middle Ages, and was not simply a nineteenth and twentieth-century phenomenon as is often assumed. Other surnames in the Rental stress this point and include the likes of de Coventre (‘from Coventry’), Newporde (‘from Shropshire or Wales’), de Parys (very possibly ‘from Paris’) and those places closer to home, including de Edebaston (‘from Edgbaston’) and de Norton (‘from King’s Norton’).

Birmingham’s thriving market attracted migrants from nearby settlements. Its nearest competition came in 1300 when Sutton Coldfield was granted a market charter. By this point, Birmingham’s market was nearly 150 years old and too well-established for Sutton to pose a threat.

As well as locational surnames, the Rental lists many occupational names which were very common in the Middle Ages. Nicholas le Sawyer would have been responsible for many of the new builds in the town. Le Sawyer means the person who saws wood, and in a place constantly attracting new migrants, homes would have been in demand.

Another new build, but this time workers are ‘raising the cruck’, which refers to the ‘A’ frame wooden beams they are hauling into place. The other common type of building was the ‘box frame’ to the left of the cruck.

One thing that tied all these people together were the rents they paid to William de Birmingham. But, even William wasn’t top of the tree. Above him were the Lords of Dudley from whom he held the manor of Birmingham, and above all of them was the king.

Having access to such a valuable document like the Borough Rental will help people to make more sense of the objects on display in the new History Galleries. While we don’t know the biography of people’s lives in the medieval town, we can make links through their professions, where they lived and even the names we share with them. We can identify with their daily struggle to pay the rent and put food on the table, and while we can never fully ‘know’ them, we can learn more than we ever could have hoped for, simply because of the discovery of this document just a few years ago. It just makes you wonder what else is out there, above ground and below!

Once again, special thanks to our model makers, Eastwood Cook http://www.eastwoodcook.com/

Sarah Hayes, Freelance Curator

Follow me on Twitter @CinnamonLatte17 to keep up to date with the latest developments on the Birmingham History Galleries.

This blog first featured on Posterous in July 2012, http://birminghammag.posterous.com/exploring-medieval-birmingham-part-ii

Exploring Medieval Birmingham

Posted: August 10, 2012 Filed under: Medieval History, Uncategorized | Tags: Archaeology, Birmingham, British History, History, Medieval, Museum Leave a commentA scale model allows visitors to depict a scene in a way that words or illustrations sometimes fail to do. To put it simply, it does all the hard work for the viewer by giving them a unique perspective that allows them to survey a landscape in its entirety. We wanted to do exactly that for our visitors at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. The model we recently commissioned for the new History Galleries illustrates what Birmingham might have looked like in 1300. ‘Might’ is deliberately used here because there are some physical features of the town for which we simply have no concrete evidence. For instance, we don’t know what the fabric of the buildings looked like and whether these buildings were front side or gable end onto the street. Timber framed buildings from the 13th century rarely survive. In Birmingham’s case, its oldest timber framed building is the 15th-century Old Crown Pub in Deritend. Nevertheless, we’ve done what historians do best! We’ve used the abundant evidence we have relating to 14th-century buildings and the limited knowledge from the 13th to produce a ‘most likely’ case scenario.

Model of medieval Birmingham in 1300. Notice the familiar triangular shape to the left of the model, which you can still see today as you walk downhill from New Street to St Martin’s Church.

Some people may be thinking ‘why not just focus on the later medieval period, for which we have more evidence?’ Well, we do have one tangible piece of factual evidence which we’ve based the blueprint of the model on. That is a document called a Borough Rental dating from 1296. This recently discovered document lists the names of townspeople who rented plots of land in Birmingham from the lord of the manor. It also tells us that there were 250 dwellings in Birmingham in 1296. Using this record, along with research from specialists, George Demidowicz and Mike Hodder, we have been able to map rented plots of land that existed in the town. These areas were known as ‘burgage plots’ and in some cases we can pinpoint exactly where certain townspeople lived.

The distinctive long and narrow burgage plots were a common feature of medieval towns. You can also see the ‘half’ plots, where land has been subdivided because of population growth or simply to generate more income.

One such person is Roger le Moul, the wealthiest merchant in 13th century Birmingham. Not only did he own 17 plots, he also gave his name to one of the best known streets in Brum: the Moulestrete of 1437 is today’s Moor Street. Birmingham, a place many assume emerged out of the Industrial Revolution was already thriving in the 13th century and this legacy is embedded in the surviving place and street names of the modern city! Our model, however, doesn’t show the full extent of medieval Birmingham. We’ve simply focused on the market place, the heart of the town, and the burgage plots that surrounded it.

A man who means business! Roger le Moul’s courtyard house, located on what later became Moor Street.

The Borough Rental also helpfully identifies the locations of Birmingham’s early industries, demonstrating why they were situated where they were. Tanning pits, a necessary component of the leather industry were located on Park and Edgbaston Streets. These streets were on the edge of the town and were ideal locations for such a noxious and smelly trade that used urine and animal faeces. Similarly, pottery making, another important early trade was located on the periphery of the town (on the site of Selfridges car park today) because of the fire hazards associated with the craft. In this way, the model really helps to emphasise the rationale of early town planning.

The beauty of our model is that it will help to dispel the myth that there was nothing here in the Middle Ages, when in fact we know that Birmingham was a bustling market centre and home to around 1,500 people. So, if you want to meet William de Birmingham, Richard le Couherde or Isabell le Sonster amongst many other medieval Brummies, visit the new Birmingham History Galleries this October and immerse yourself in the medieval history that made our modern city.

Whether keeping animals, growing food, dying cloth or making pottery, people’s back yards really were places of activity in medieval Brum.

Look out for my next blog which focuses on the interactive features of the model. You can see the model on display this October in the new Birmingham History Galleries, Birmingham, its People, its History.

Special thanks to our model makers, Eastwood Cook http://www.eastwoodcook.com/

Sarah Hayes, Freelance Curator

This blog first featured on Posterous in June 2012, http://birminghammag.posterous.com/exploring-medieval-birmingham